Why Is My Bread So Dense? How To Fix Dense Bread

Why is my bread so dense? All day, I’ve followed a recipe, made a mess, kneaded, cleaned, proofed, and cleaned again to put my loaf in the oven. Yet upon removing my loaf from the oven, I slice it to find that my bread is dense and heavy like a brick – and looks nothing like the photo!

If this sounds like your last bake or if your bread is constantly failing in the light and fluffy department, don’t worry. It’s all part of the learning process!

Use this article to troubleshoot your dense loaf; together, we’ll break down where you went wrong!

Why is my bread so dense?

So what can you do to prevent your bread from turning out dense? Well, let’s look first at the causes of dense bread.

Bread becomes dense when not enough gas is retained in the bread dough. The reasons for this are vast, but they always come down to the following:

1) Not enough gas produced (a gas production issue)

or;

2) Not enough gas captured (the dough has poor gas retention qualities)

So whatever the cause, not producing or retaining enough gas is where it went wrong.

For bread to rise, yeast processes sugars in the dough to create (carbon dioxide) gas. Flour is moistened with water and develops a gluten network to capture the gas created. The network stretches and expands as more gas is produced, forcing the dough to rise.

If a good gluten network is formed (to capture gas) and the dough can fully rise, you’ll make perfect bread. Not dense bread!

So, how to make your own bread less dense?

Now you know the basics of why homemade bread becomes dense, let’s cover solutions for how to make bread less dense, starting with the most common.

1- Proof your dough for longer

Under-proofing is the most common cause of a dense (and occasionally, gummy) crumb texture. A rushed final rise produces less gas, making the crumb compact and dense.

To resolve under proofing, let your bread rise longer the next time. In most cases, this alone will fix your dense bread.

How to prevent under-proofing with the poke test

Use the poke test to tell when bread is fully proofed by poking the dough with a wet finger. If it springs back right away, it needs longer to rise. The bread is ready to bake once the poke leaves an imprint for 2-3 seconds before bouncing back.

The poke test works well in most instances. However, different dough types behave differently. If you follow the poke test and the bread remains dense, proofing longer still next time can help. Just be careful to avoid signs of over-proofing!

Tip: The poke test does not work when prooofing dough in the fridge.

How to avoid over-proofing

If your bread collapses in the oven (or just before), it was proofed too long and will have a crushed or compact crumb.

When dough begins to over-proof, translucent bubbles appear on the surface. These bubbles form when gas has expanded weak areas of the gluten structure. If you notice them, quickly get your bread baked, it might be ok! But if it’s too late, the over-proofed bread will collapse, leaving a compact, dense crumb. This is because:

- Too much carbon dioxide is produced, making the dough heavier

- The protease enzyme in the dough eats away at the gluten strands

- Lactic acid bacteria break down the gluten strands

- As the sugar supply depletes, yeast consumes gluten proteins instead

The result is: The yeast continues to produce gas, but the weak and heavy structure can’t cope, and the dough collapses. If this happens, reduce proofing duration in future.

2- Create a better environment for your yeast

Aside from poor gas retaining properties (we’ll come to this later), if bread dough rises very slowly or not at all, it’s because:

- The proofing temperature was too cool

- The yeast was out of date

- Too much salt or sugar was used

- There wasn’t enough yeast in the recipe

All four points lead to yeast creating gas at a slower rate. Patience runs out, and the tendency is to bake bread prematurely when it is “under-proofed”. Aside from this, a slow rise can lead to the gluten deteriorating before enough gas is retained.

To prevent this from happening, let’s address the points above to create the best conditions for your bread to rise.

How much yeast do I need in a bread recipe?

Most bread recipes use around 2% of yeast. In bread baking, recipes are worked out as percentages against the total amount of flour used, so if a recipe contains 500 grams of flour, and the 2% rule for yeast is followed, 10 grams of yeast is used.

The amount of yeast varies depending on the bread being made.

If you slowly develop your dough with a long double-rise, 1.4-1.6% yeast is recommended. For recipes that contain lots of sugar or heavy inclusions such as dried fruit, nuts or protein, use 2.5-3.5% yeast. These guidelines are for fresh yeast.

If using dried yeast, do a yeast conversion. See the table below:

| Fresh Yeast | Active Dry Yeast | Instant Yeast | Osmotolerant Yeast |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 44% | 33% | 28% |

| 30 grams | 13.2 grams | 10 grams | 8.4 grams |

| 10 grams | 4.4 grams | 3.3 grams | 2.8 grams |

| 5 grams | 2.2 grams | 1.7 grams | 1.4 grams |

| 3 grams | 1.3 grams | 1 gram | 0.8 grams |

How much salt and sugar to use in bread dough?

Salt and sugar divert water from the yeast cells, slowing the rate of yeast activity. Salt is essential for flavour and strengthening the gluten structure. Without salt, bread dough will rise outwards, not upwards.

Most bread recipes use 2% salt. Again, that’s 10 grams of salt for every 500 grams of flour. Sweet bread types typically use less, around 1-1.6%. Some artisan bread uses up to 2.2% to provide a favour boost. Bread will taste saltier and rise slowly when more salt is used.

Sugar usage varies. It’s not an essential ingredient in bread making, but adding sugar to bread has many benefits. 2% of sugar will lighten and speed up the rise of yeasted bread. For sweeter bread types, use more.

If a bread recipe uses over 5% sugar, the action of the yeast is reduced severely. Add more yeast or use specialist osmotolerant yeast.

How to warm dough during proofing?

The best bread proofing temperatures fall within 25-38C (77-100F). However, without a recipe specifically formulated for the Chorleywood Bread Process, it’s best to stay within 25-35C (77-95F).

Flour contains enzymes. Enzymes are also produced by yeast. Enzymes are proteins which accelerate (catalyst) the breakdown of starch into simple sugars. Once broken down, yeast will process the sugars to make gas.

In cooler temperatures, enzymes and yeast cells work at a slower rate. Therefore, when proofing dough at cooler temperatures, fewer sugars are produced, and less gas is created, so bread takes more time to rise.

Warm your dough during proofing to avoid under-proofing or the weakening of the gluten structure. And the guys at Brod & Taylor have the solution if you bake one or two loaves at a time! It’s a proofing box where you can set the temperature you want to proof, let it warm up, pop your dough in and not have to worry about it being too cold to rise!

Head over to Brod & Taylor to see the latest deals, or try Amazon.

If you make larger batches or like a bit of DIY, success can be enjoyed by making a DIY proofing box.

Setting the proofing temperature removes a common cause of slow-rising bread. You can also experiment with different proofing temperatures and timetables to tweak the flavour of your homemade bread.

Honestly, get one or build one. Baking bread is so much easier!

3- Activate your yeast

If you’ve taken the previous steps, but there still seems to be a lack of gas created, it could be that your yeast has expired or needs activating (blooming).

Active dried yeast must be activated (bloomed) to unleash its full potential. See my guide on how to bloom yeast.

If unsure if your yeast is active, add your yeast to warm water. If, after 10 minutes, there are bubbles, you’re all good! If not, ditch it and try another.

If your bread is not rising at all, see why did my bread not rise article.

The sourdough starter was not ripe

If your sourdough bread did not rise or was very slow to rise, your starter is probably the problem. Before raising bread, sourdough starters must develop plenty of active yeast cells and Lactic Acid Bacteria.

A typical starter takes 3-4 weeks of regular feedings to achieve the necessary maturity required to raise bread. It should double, if not triple, within 6 hours of feeding and smell fragrant!

If this is not the case, refresh your sourdough starter for a few more days before trying again or view my sourdough starter is not rising guide.

For help with dense sourdough bread, I have a full guide!!

4- The first rise was too short

“80% of the quality of the bread is the quality of the dough”

There are several ways to make a loaf of bread. A critical decision is whether to double rise or not.

Many bread recipes, including my beginner’s bread recipe, separate proofing into two rises.

The first dough rise is called “bulk fermentation”. Here, the dough is placed in a container to mature after kneading. Once the baker is happy with the development of the dough, bulk fermentation ends, and the dough is divided into individual pieces. They are shaped and proofed for a second time in a tin, tray or banneton-proofing basket until ready for the oven.

Why does double-rising dough matter?

During bulk fermentation, yeast undergoes anaerobic respiration, leading to ethanol fermentation, where carbon dioxide gas and ethanol are produced.

Bread dough is the perfect environment for Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB). During bulk fermentation, LAB multiplies. Alongside yeast, the bacteria ferment sugars in the dough to produce organic compounds, such as lactic acid, acetic acid, vinegar and carbon dioxide.

Benefits of this dough maturity include:

- Improved gluten extensibility

- Better handling capabilities

- More depth of flavour

- Improved shelf life

So, in essence, you’ll get better gas-retaining properties when you double rise, but you can still make a light and fluffy loaf with a single rise. The key is kneading!

Note: Further benefits for double rising are discussed in the dough fermentation post

5- Knead your dough for longer

The dough’s gluten network develops over time during the first rise but can be accelerated by kneading. We can reduce or even eliminate the bulk fermentation stage by kneading dough intensively.

The result is well-aerated, lighter bread that’s made quickly.

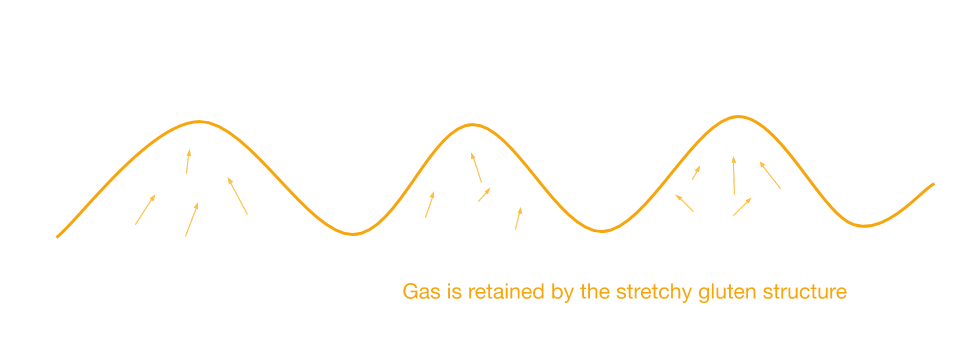

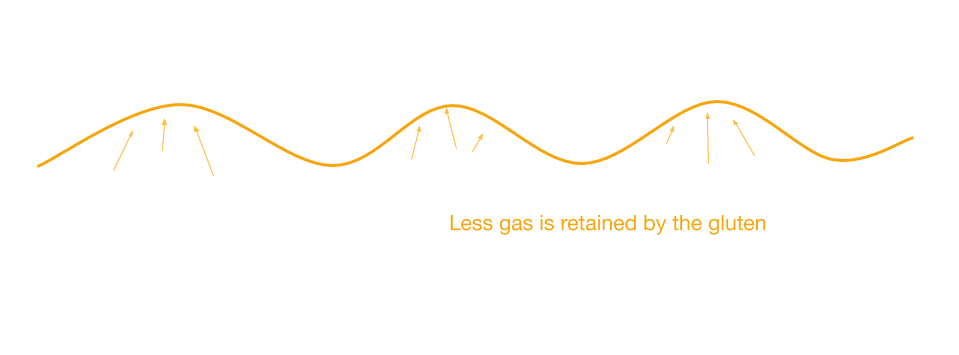

Gluten is the main protein in wheat flour. In their dry state, gluten strands are tangled in irregular coils. When wet, the strands soak up water, extend and straighten. Existing bonds between strands are broken, and new bonds appear, forming a network of tiny air pockets capable of retaining gas.

You can see in the images below that extensible gluten retains gas better.

An extensible gluten structure:

A less extensible gluten structure:

When double-rising, the gluten structure naturally improves. Gluten network maturity alongside fermentation activity enhances the ability of the dough to capture the gas. Kneading accelerates the process whilst also pumping oxygen into the dough.

A well-kneaded dough requires less bulk fermentation for optimum gluten development. Yes, less yeast fermentation means the gluten will be less mature and the bread less flavourful. However, this doesn’t mean it can’t capture enough gas to make a light and fluffy loaf.

You can’t knead well and bulk ferment for several hours. This will lead to the gluten structure over-oxidising and/or collapsing.

You must choose between 1) kneading well and single rising, 2) lightly kneading and double rising for 6+ hours, or 3) medium knead duration followed by a 1-2 hour bulk rise.

Tip: No-knead recipes use the lightly kneading and double rising for 6+ hours method. You can see my no-knead bread recipe here.

How to knead bread properly

To knead a dough for a single rise, 10-20 minutes of hand kneading is necessary.

I split hand kneading into three stages: the incorporation of ingredients, slow mixing to hydrate the gluten, and the final stage, intensive kneading.

See my how to knead dough guide for more.

In a dough mixer, use a slow mix for 3-8 minutes, followed by a faster speed for 5-8 minutes. See how long to knead bread dough.

How to measure gluten development in dough?

Whether you double-rise or not, aim to achieve full gluten development when it’s time to shape. Use the windowpane test to measure gluten development.

The windowpane test:

Remove a piece of dough and stretch it out with your fingers. It should be firm, soft, elastic and smooth. It should not rip at the first instance.

When dough stretches thin enough to let light pass, it passes the windowpane test (100% gluten development). If not ready, knead or bulk ferment for longer.

6- Use stretch and folds during bulk fermentation

Stretch and folds can be applied during bulk fermentation. They accelerate gluten development and increase fermentation activity by stretching and re-aligning the gluten matrix, redistributing the ingredients and redistributing warmth in the dough.

All pretty handy I hope you’ll agree!

To do a stretch and fold, follow the steps in the video below:

Repeat the action every 30 minutes during the first rise.

Tip: See the sourdough stretch and fold page for advanced methods.

Inspect your crust

A thin crust means a bigger oven spring, crispy crust, and more moisture can escape. Check your crust after baking. If it’s thick and moist, more gluten development next time should improve things.

7- Bulk fermentation was too long for your flour!

When repeating a bread recipe with new flour, it’s common for the dough to collapse during bulk fermentation. This is because the flour has a lower W-factor than the previous one.

The W-factor measures how long flour can withstand fermentation before it tears. You’re unlikely to know the W-factor of your flour as millers (frustratingly) avoid printing it on their packaging.

The W-factor is linked to the amount of protein. Flour with a high percentage of protein usually has a higher W-factor, but the protein quality produces the figure.

If your bread collapses, shorten the bulk fermentation time or try another flour brand.

How long should bulk fermentation last?

A typical first rise duration will be 2-6 hours at 20-25C. Typically, you are looking for the dough to rise 50% before ending bulk fermentation. The challenge is getting the dough to rise to its intended height at the same moment that the gluten reaches 100% development.

Timings depend on the proofing temperature, how aggressively the dough was kneaded and the amount of yeast used in the recipe. Placing the dough in the fridge cools the dough, making the yeast less active so one can be left overnight.

8- After mixing, the dough was too hot or cold

When the dough is cold, it’ll take longer to rise.

If the dough is too warm, yeast will produce gas during kneading, making a wet, sticky dough that’s hard to knead, resulting in less gluten development as kneading is cut short. A warm dough can also cause the dough’s sugar supply to run out early, so the dough doesn’t fully rise.

Most bread types have an optimum dough temperature of around 25C (77F). To control the temperature of your dough, use a formula to calculate the post-mix dough temperature and adjust the temperature of your water before you add it to the mixing bowl.

To do this, take temperature readings (this thermometer from GT-Dealer is perfect) of the flour and the room. Then, use a desired dough temperature formula to calculate the water temperature. Use hot or cold water to adjust its temperature before weighing.

WT = Ideal Water Temperature DDT = Desired Dough Temperature (25) RT = Room Temperature FT = Flour Temperature 3 x DDT - RT - FT - 18 = WT

9- Use bread flour

Another reason for bread dough not retaining enough gas or collapsing is using the wrong flour. It is best to use high-protein bread flour for making bread as the extra protein content forms a more defined structure that can capture carbon dioxide.

There is a caveat to this: not all flour protein is suitable gluten (glutenin vs gliadin), and not all gluten is in good condition (some of it is damaged)… But we’re ending down a rabbit hole here, so use good bread flour from a reputable source.

I have great success in the UK with Shipton Mill and Wessex Mill, but there are plenty of others.

Can I use whole wheat flour to make bread?

You can, but a 100% whole wheat loaf that isn’t dense is hard to achieve. Most bakers combine baker’s white flour and whole wheat flour. See how to do this and many other tips for working with whole wheat flour in how to make whole wheat bread less dense.

Can all-purpose flour make light and fluffy bread?

Low-protein flour forms a weaker gluten structure. However, in bulk fermentation, damaged proteins are repaired. This means flour with less protein can be used for longer-fermented bread, but not longer than 6 hours, as the gluten will begin to degrade and perform much worse (see w-factor)

All-purpose flour that is grown in North America is high in protein regardless. It can make light bread, but specialist bread flour often produces better results.

A table comparing flour types and uses:

| Flour type | Protein % | Use |

| Super high protein | <14% | Quick bread or where elasticity is required in long-fermented doughs such as pizza or high-hydration doughs like ciabatta |

| Bread flour | 12-14% | Quick bread, such as tin bread and rolls |

| Strong all-purpose flour | 11-13% | Medium fermentation loaves such as sourdough, focaccia, baguettes |

| Weak all-purpose flour | 10-12% | Long fermented bread such as sourdough |

| Cake flour (UK plain flour) | 8-10% | Cakes and pastry |

If you can’t get bread flour where you are, vital wheat gluten can be added to boost weaker flour.

10- Measure your ingredients accurately

There are a lot of variables in baking bread, so don’t introduce any more with inaccurate measuring! If you use measuring cups to portion your ingredients, you can easily add too much flour (or too little) or other ingredients, causing many issues, including an overly-compact crumb.

Weighing the ingredients with a metric scale is the best way. You should also weigh liquids too. It’s much more accurate!

The scales that I recommend are from the KD range by My Weigh. They have a simple design, can be plugged in or battery-powered, and chunky buttons are great when rushing around.

11- Adjust the amount of water used in your dough recipe

If your dough doesn’t contain enough water, gluten will be damaged during kneading, preventing it from becoming extensible.

Too much water makes the gluten swim, making it unable to support the weight of an aerated structure.

If you end up with a soupy mess or a dough that’s too hard to knead, adjust the quantity of water next time. Different flours absorb water at different rates and quantities, but as a general rule when changing flour:

If the flour’s protein content increases by 1%, use 5% more water

12- Prefect your shaping technique to make lighter bread

How bread is shaped will affect how it rises. To shape bread dough properly, break it into three stages:

- Preshaping

- Bench rest

- Final shaping

The first stage of shaping is preshaping. This involves pushing the gas out of the dough and shaping it into a ball or batard shape.

The bench rest period lasts 10-30 minutes, allowing the gluten to relax to hold its shape when shaped again.

The methods used for final shaping create tension in the dough’s outer perimeter (crust area). The stress supports the shape as it rises, forming a thinner but firmer crust in the oven.

If shaping is not perfected, the dough will spread outwards as it rises, creating a badly risen and dense loaf.

Shaping sourdough bread

If you are looking for large erratic bubbles through the crumb (as in many sourdough loaves), you may push bulk fermentation until the dough has risen over 50%. This makes the dough gassier when shaping.

In this case, care must be taken when preshaping and shaping to keep the gas in the dough whilst creating enough tension. If too much gas is removed, the yeast may not have enough sugars to produce enough gas to replace it!

13- Improve your oven for a bigger oven spring

Changing how you use your oven could be the best way to fix dense bread.

Bread rises during the first 10-15 minutes of baking, called “oven spring”. During the early stages of baking, the warm environment makes water in the dough evaporate. The water vapour rises upwards, pulling the bread with it, so it rises 20-50%.

We need oven spring to increase volume and stretch the outer perimeter, making a thin and crispy crust that moisture can escape the crumb.

If your bread doesn’t rise much in the oven or has a thick-hard crust, you will likely find that your bread has a dense, damp, crumb texture.

Getting the perfect bake on bread is often the difference between ordinary homemade loaves and ones that look professional. Just because you are baking at home doesn’t mean you must miss out!

Baking stones

Many homebakers place a baking stone in their oven. These will be preheated for around 1 hour to improve heat distribution and conduction in your bakes.

Heat conducts through the base of the bread, improving oven spring volume and preventing a damp crumb and a soggy bottom.

If you don’t have a baking stone, preheat your thickest baking tray. However, I recommend getting a baking stone as soon as you can. It improves the oven spring so much. I wouldn’t bake bread without one!

The one below is durable, thick and has excellent heat distribution:

Creating steam

Oven spring is more prolific when the oven is warm and humid. Moist air protects the bread’s outer perimeter, preventing it from hardening immediately. It also reduces heat conductivity, extending the baking time and making a crisper crust.

If the air inside an oven is dry, there is less oven spring. The bread bakes faster, creating a more compact crumb and a moist, dense texture.

To create humidity in an oven, the most common method is to use a water mister to spray inside the baking chamber ( 3 seconds constant or five spritzes is enough).

Another option is to place a deep-lipped tray filled with water on a lower oven shelf before baking. Once the oven is filled with steam, place your dough to bake.

After 20 minutes, the steam is released by opening the door (damper on a professional oven) for a few seconds or removing the water bath. The crust can then harden to make the crust crispy.

14- Score your dough before baking – quickly!!

Scoring well-proofed bread dough creates a route for excess gas to escape. Not scoring, or not scoring deep enough, leads to the crust rupturing as gas builds up in the oven.

Scoring too deeply or making too many cuts leads to excess gas escaping, preventing your bread from rising fully in the oven.

A specialist knife called a lame produces laser-sharp cuts to make bread look amazing!

15- Cool your bread to stop dense bread

Cooling is a commonly overlooked stage of bread making. Slicing into your bread before it is ready or improper cooling can make bread stodgy and dense.

Bread should be cooled with air flowing so moisture can escape.

Wait until your freshly baked bread has dropped below 35C (95F) before slicing for the best results.

Tip: Some home bakers cover their bread with a tea towel as it cools. This keeps moisture in the bread to soften it. The trade-off is the bread becomes denser.

Other ways to fix dense bread

We’ve covered the common faults that make bread dense, but there are other things you can do to make your bread lighter. Here are a few tips to try:

When kneading, delay the addition of fat

Fats benefit dough with their tenderising and flavouring attributes. However, they lubricate the gluten strands, which protects gluten when kneading.

When using more than 5% of fat in a bread recipe, add it to the mixing bowl when kneading is almost complete, then knead it until absorbed.

Vegetable oils or other liquid fats contribute moisture to the dough. Delaying their addition will under-hydrate the dough and damage the gluten proteins. To avoid this, sometimes there is no other solution than adding the fat at the start of mixing. Just try your best to delay them!

Avoiding over-kneading bread dough

Just as under-kneading bread dough creates issues, so does over-kneading. If your dough gets noticeably weaker, it was over-kneaded, over-fermented or a combination of the two.

To avoid over-mixing, use the same flour each time you bake to understand what it needs. A countdown timer is handy to remind me to check my dough.

Keep working on the same recipe!

Instead of ditching a recipe every time it fails, choose one from a reliable author and keep repeating it until you master it!

Look for bread-baking experts such as Yeast, Tartine and popular baking blogs such as The Perfect Loaf or (shameless plug) my bread recipes!

Why is my bread so dense? – Ending thoughts

We’ve progressed through many stages of making the perfect light and fluffy loaf in this article. I hope you’ve answered the original question, “Why is my bread so dense?” you probably have many things to work on. I hope your bread going forward is a roaring success!

If you’ve enjoyed this, keep in touch by signing up for my newsletter and drop a comment below if you have any questions!

If you’ve enjoyed this article and wish to treat me to a coffee, you can by following the link below – Thanks x

Hi, I’m Gareth Busby, a baking coach, senior baker and bread-baking fanatic! My aim is to use science, techniques and 15 years of baking experience to make you a better baker.

Table of Contents

- Why is my bread so dense?

- So, how to make your own bread less dense?

- 1- Proof your dough for longer

- 2- Create a better environment for your yeast

- 3- Activate your yeast

- 4- The first rise was too short

- 5- Knead your dough for longer

- 6- Use stretch and folds during bulk fermentation

- 7- Bulk fermentation was too long for your flour!

- 8- After mixing, the dough was too hot or cold

- 9- Use bread flour

- 10- Measure your ingredients accurately

- 11- Adjust the amount of water used in your dough recipe

- 12- Prefect your shaping technique to make lighter bread

- 13- Improve your oven for a bigger oven spring

- 14- Score your dough before baking – quickly!!

- 15- Cool your bread to stop dense bread

- Other ways to fix dense bread

- Why is my bread so dense? – Ending thoughts

Related Recipes

Related Articles

Latest Articles

Baking Categories

Disclaimer

Address

53 Greystone Avenue

Worthing

West Sussex

BN13 1LR

UK