The Stages Of Bread Making

No matter which bread recipe you follow, each one follows the same stages of bread making. It’s not common for a bread recipe to utilise each stage, with some fantastic recipes only using 7-8 of the 13 stages. Adding a step won’t necessarily make a beginner’s bread recipe better, but if you are new to bread baking, it’s handy to know what happens in each step!!

Baking bread doesn’t get more complicated than this, so if you can understand the stages of breadmaking, you can quickly become a bread master! In this article, we’ll cover what happens during each phase and how the bread benefits from utilising them.

The 12 stages of making bread:

- Creation of the levain

- Weighing of ingredients – Mise en Place

- Autolyse

- Kneading

- Bulk fermentation

- Dividing

- Shaping

- Final proof

- Scoring

- Baking

- Finishing

- Cooling

1. Creation of the levain

The most popular levain used in bread baking is yeast, though there are others.

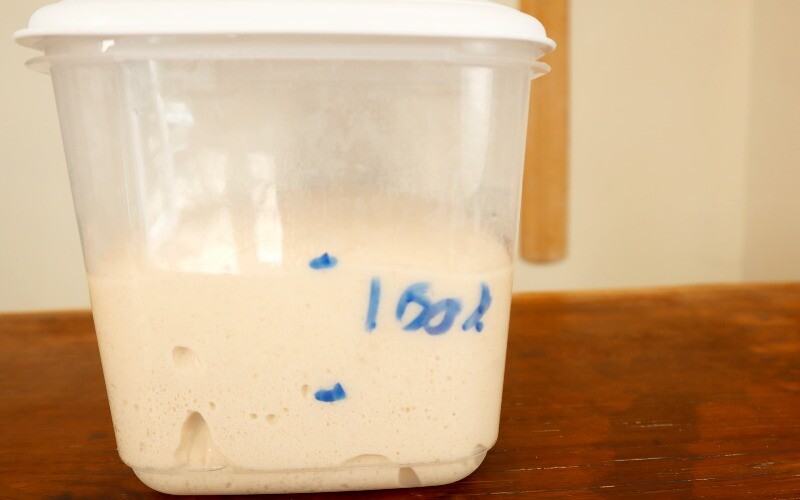

Many artisan bread recipes use a prefermented levain or sourdough starter. The preferment is a combination of flour, water and (usually) a little bit of yeast. In the case of a sourdough starter, it is discarded and refreshed with fresh flour and water.

The mixture is left for 2-18 hours for the yeast to multiply and ferment. This develops flavour and conditioning properties in the dough. More advantages are described here: what is a levain?.

For “straight doughs” a preferment is not used.

2. Weighing of ingredients – Mise en Place

Mise en Place is French for “everything in its place”. This means it’s time to get the bowls, equipment, recipe, ingredients, and yourself ready to bake.

When making bread, good organisation is essential. There’s nothing worse than realising the yeast has expired or you have no work surface to knead!

Get your ingredients weighed, bowls ready and the work area tidy.

3. Autolyse

Autolyse is a process of combining the flour and water in a bread recipe and leaving them for around 10-60 minutes, sometimes longer. The levain can also be added or left out. The salt is usually omitted and added at the end, but some choose to add it for the autolyse for a different effect.

The Autolyse method hydrates the gluten strands, allowing them to unwind and extend to form a strong gluten network. Naturally occurring enzymes activate and break starch into smaller sugars, ready to be processed by the yeast. Enzymes also break down some gluten proteins, making the dough more extensible (stretchy) after autolyse.

Once the autolyse period ends, the remaining ingredients are introduced, and kneading begins.

Further reading: Soaker or autolyse – what’s the difference?

4. Kneading

I divide kneading into three stages. The first is the “incorporation stage”, then “slow mixing”, and finally ” fast kneading”.

The three-pronged approach encourages the gluten structure to develop into a well-hydrated, strong structure that will retain gas. Good gas retention qualities are vital for good bread dough. Proper kneading is where good dough begins.

Bakers can increase or decrease the time and intensity of kneading. Different dough mixer speeds or changing their hand kneading technique alter the intensity. How dough is kneaded changes the characteristics of the bread, even when the same ingredients are used. The amount of kneading that a dough undergoes is referred to as gluten development. 100% gluten development is when the dough is ready to be moulded and proofed right away, whereas a lower level of development will require more kneading or a longer bulk fermentation (the next step).

Towards the end of mixing, extra ingredients can be added that would have been crushed if added at the start. Common additions include; dried fruit, olives, cheese and herbs.

Another kneading method I like is bassinage. This is where extra water is added near the end of kneading, which makes the bread crumb more irregular.

The addition of fat is often delayed until the end of mixing. Fat makes it hard for the gluten to develop when kneading. Delaying the addition of fat till the end of kneading will improve the gluten structure.

Further reading: Why knead bread? – The windowpane test – Desired Dough Temperature – Can I add extra flour when kneading? –

5. Bulk fermentation

Bulk fermentation is also known as the “rest period” or “first rise”. It’s a stage that sounds complicated and lasts from ten minutes to two or three days.

All you have to do to bulk ferment bread dough is place the dough in a container to rest. It’s then covered and stored, preferably at a constant temperature. Many things occur during this stage. Its purpose is to mature the dough to be ready for the final rise:

Enzymes

Naturally occurring enzymes break down the complex starches in the flour into simpler sugars. Yeast uses simple sugars to create carbon dioxide and often ethanol too. Carbon dioxide makes the bread rise, whilst ethanol improves flavour.

Organic maturation

Bulk fermentation supports the development of lactic and acetic acids. These organic acids are produced when acidic bacteria multiply and ferment sugars in the dough. They aid flavour, keeping quality, gas retention and many other benefits. They can produce carbon dioxide too!

Gluten development

Allowing gluten to absorb water slowly enables it to form a strong gluten matrix. Kneading is responsible for a lot of gluten development, yet it can be complemented with bulk fermentation to continue developing. Gas produced by yeast stretches the gluten strands, making them stronger and extensible.

“Stretch & folds” or “punching down”

Bakers use stretch and fold’s during bulk fermentation. These strengthen the gluten structure by realigning the gluten strands. Stretch and folds redistribute temperature and the ingredients throughout the dough. This helps to form a contestant environment and supply of food (simple sugars) for the levain.

“Punching down” is a version of a stretch and fold where the dough is punched before shaping. This forces the gluten structure to rebuild. However, stretch and fold techniques are more effective.

These processes combine with others to produce a mature dough that’s better at retaining gas and holding shape as it rises. You can find out more (and why skipping this step can be beneficial) in the bread fermentation process article.

Further reading: Why cover dough? – How long can dough sit out?

How do no-knead recipes work?

Some recipes follow a “no-knead” technique where the ingredients are gently incorporated before being placed in a bowl to bulk ferment for an extended period (typically, 8 hours plus). During this time, the dough structure forms, and fermentation activity provides extra flavour.

6. Dividing

If making more than one piece of bread from a batch of dough, the dividing stage is when you’ll split your batch into individual pieces. When dividing, it’s best to use scales, so each dough piece weighs the same. If you don’t have scales, you can “eyeball it”, but results are rarely accurate.

Take the dough from its resting place and turn it onto a lightly floured work surface. Get the scales out, and use a metal dough scraper to cut and remove a piece of dough that’s approximately the weight you’ll need. Place it onto the scales and add or remove dough until you achieve your desired weight. A 5% tolerance up or down is usually used.

The expected dough weight should be provided in the recipe. If not, see making bread in bulk for common examples.

Instead of flouring your work surface, an oil slick is a great alternative, as it doesn’t risk incorporating raw flour into the dough.

Further reading: Is it safe to eat raw flour?

Top tip: Plan your bake

It’s a good idea to plan ahead before you start baking. You don’t want to be doing something else when your dough needs attention. Design a schedule that fits around your bake. This way, you’ll remember to check on your dough and turn the oven on etc. This leads to a more enjoyable experience and making better bread.

7. Shaping

Homemade bread loaves are usually shaped twice. Double shaping gives the dough the strength it needs to hold its shape during its final rise.

Preshaping involves taking a piece of the dough and shaping it into a ball or cylindrical shape, known as a “batard”. The dough is “degassed” during preshaping to remove pockets of gas. A long-fermented dough (long bulk rise) will likely contain more gas, therefore, shouldn’t be degassed as much as quickly-made bread dough.

To remove more or less gas when shaping, push or less air out of the dough.

After preshaping, the dough piece is left on the work surface, covered with a towel or sheet of baking paper.

The bench resting takes 10 to 30 minutes. A more mature (and gassy) dough should be left longer than a quick bread so the gluten can relax, but not so long that it loses its strength.

After the bench rest, it is time for final shaping. Here, the dough is flattened on the work surface and then moulded into the desired shape. The moulded dough is then placed in its proofing basket (or tin, board, tray, bread tin etc.), ready for the final proof.

Here’s how dough is shaped when making tin bread:

8. Final proof

Now it’s time for the levain to raise the bread. The “final proof“, “final rise”, or “proofing” (all the same) can last a matter of minutes to several hours. Most basic bread loaves take around 2 to 3 hours at room temperature to rise.

The final rise is temperature dependant as yeast becomes more active when warm. To speed up the rise, the amount of yeast and/or the bread proofing temperature can be raised. Many home bakers warm their proofing environment using an oven with only the light on or building a DIY proofing box.

In a professional environment, a proofer is used for the final proof. This is essentially a box that maintains temperature and humidity to create the perfect proofing environment for the bread.

Humidity is important, mainly to prevent the bread from drying up and forming a skin, but also because the free water can act as a carrier between cells in the dough.

Bakers without a humidity-controlled proofer must cover proofing dough with a plastic bag, shower cap, box lid -or something to reduce exposure to airflow.

The Brod & Taylor home proofer has been a game-changer for many home bakers in recent years. It allows you to control the temperature with degree precision! You can even make the proof box humid with its fitted steam pot.

See Brod & Taylor’s website to learn more, or check them out on Amazon.

Alternatively, the proofing temperature can be cooled, and the rise slowed. This method usually means an overnight rise, partially conducted in the fridge in summer, or simply left on the counter in cooler seasons and climates. A longer rise usually leads to more flavour and either a sweeter or more acidic bread.

Note: There's an extra stage whilst the bread is rising - do the washing up!

How to tell when bread is ready?

The most popular way to tell if bread is ready to bake used by home bakers is the poke test. Here the dough is gently poked with a wet finger and retracted. If an indent remains for 2-3 seconds before springing back, it’s ready to bake. If it springs back right away, it can be proofed longer, but when it stays down for longer than 3 seconds, it is over-proofed.

If you want to see common proofing times for particular bread types, see my proofing guide tables.

9. Scoring

Once the dough has reached its intended size, it is scored before entering the oven.

Tip: If proofing in a banneton, before scoring, the dough is tipped out onto a board or baker's peel. When a loaf tin or tray is used, the dough is not tipped.

Cutting through the surface of the dough with a sharp blade allows gas to escape during baking. See, during the early stages of baking, yeast rapidly produces gas due to the warmth. Much of the extra gas produced is retained in the dough, making it “spring” up, which is why it is called “oven spring”.

Scoring stops excessive amounts of gas from exploiting weak points in the dough and rupturing the crust. As white loaves have a plethora of simple sugars available to feed the yeast, they produce the most gas during oven spring.

Whole wheat doughs made from wheat and other whole grain flours (rye and spelt) produce less gas during oven spring, so they do not need to be scored.

A clean cut from a sharp blade improves the look of the loaf and the quality of the crust. To achieve this, a specialist baker’s lame is preferred, but a serrated knife will do a reasonably handsome job in most cases.

10. Baking

After scoring, it’s straight to the oven to bake!

For best results, a baking stone is placed at the bottom of the oven before preheating. It will take around 60-90 minutes of preheating for the centre of the stone to come up to temperature.

A baking stone conducts heat directly into the base of the bread. This pushes up water vapour and gas produced to maximise the power of the oven spring and bakes the bottom of the bread.

After scoring, the dough is slid onto the hot baking stone. Bread tins and rolls can be placed directly on the stone. Steam is added with a water mister (or alternative method) if required, and the oven door is closed quickly.

Adding water to the oven to create steam is vital for a crispy crust and a strong oven spring. Bread will rise in the oven by around 20% during oven spring, sometimes more. For soft-crusted bread, steam is not added.

The best oven temperature for bread is 220-230C (430-450F) for lean bread types. Lean bread is bread that does not contain enrichments such as fat, eggs and oil, or lots of sugar.

Enriched bread types are baked at around 180-200C (350-390F) is preferred for enriched doughs to reduce excessive browning (burning).

During baking, the dough structure loses moisture, making it hard. Maillard reactions and caramelisation brown and colour the crust. A dark brown or blackened crust imparts flavour and aroma throughout an entire loaf.

Starch particles cling to the gluten and water particles in the crumb. As baking continues, water passes to the crust area of the bread, where it evaporates into the oven’s air. Once enough moisture has left the bread, it is baked and ready to be removed from the oven.

Tip: The baking time is reduced in soft bread type to retain more moisture in the crumb. This makes the bread softer.

When is bread ready to come out of the oven?

When crusty bread is baked, it will sound hollow when the base is tapped with a finger. Soft bread requires less time in the oven but won’t sound hollow. Check soft bread is ready by the colour of the crust. See how to tell when bread is done for a detailed guide.

Further reading: Baking bread in a home oven guide – Stop oven issues – Fix common oven temperature problems – Heat spots in the oven – Can I open the oven door? –

11. Finishing

This stage of bread making is not used in many bread recipes, but essential when it is included!

A glaze or topping can be added to bread after baking or once cooled. A glaze (often warmed apricot jam) is applied with a pastry brush. Fruit and nuts can be sprinkled after a glaze to adhere to the sticky surface.

Note: Egg wash is a popular glaze added to unbaked dough before baking

For a savoury glaze, a drizzle of olive oil can be dripped onto the bread after baking.

12. Cooling

It can be tempting to tuck into your delicious bread when it’s warm, but a better crumb and crust texture is achieved if you have the willpower to wait! Once the bread is ready, remove it from the oven and leave it to cool.

The cooling time for bread is determined by the size of the loaf and how dense it is, but 2-3 hours is typical.

Bread continues to lose moisture as it cools, making it lose weight. See how much weight is lost when bread cools to learn more!

Tip: When removing soft rolls from the oven, give the tray a bang on the work surface. This helps them set and reduces the likelihood of wrinkles appearing.The stages of making bread – conclusion

Depending on the recipe, some stages can be skipped, doubled or increased. If you see a recipe that doesn’t follow these stages, it’s not a problem. There are very few recipes that include every step!!

What did you learn? Is there anything that you wish was included in this guide? Let me know in the comments below.

Previous: An Introduction To Bread Making

Latest Articles

Baking Categories

Disclaimer

Address

53 Greystone Avenue

Worthing

West Sussex

BN13 1LR

UK